Nationalism in Bezbaroasque literature and 19th Century Assam

Nationalism is an emotional condition or sentiment using which a social revolution is crafted involving cultural, political and economic re-organisation. Nationalism can have two variations-

- A movement to accord one’s nation an enhanced political identity post a long wave of internal conflict.

- A movement to politically liberate territory historically belonging to a national group from the control of an alien power.

Since the word nationalism or ‘Jatiyotabaad’ signifies a holistic upbringing in a nation’s socio-political worth, only political freedom should not be confused with real freedom. The notion of nationalism that originated in the 19th century has today come to be identified more with linguistic self-pride. Linguistic and cultural osmosis creates the ground for nationalistic passions to attain pronouncement and such feelings later help to shape political nationalism. One of the cornerstones for the growth of nationalistic sentiments is a common language. The vernacular press, literature and print media are other vehicles through which a process of nation building emerges.

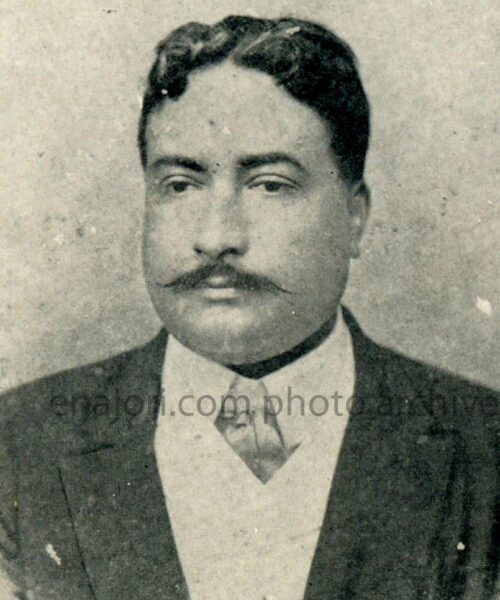

Lakshminath Bezbaroa is one of the stalwarts of the Assamese literary tradition. The beginning of his career co-incides with a very difficult period in the history of Assamese literature. Fondly remembered as ‘Sahityarathi’ and ‘Roxoraaj’ he is without a doubt the one who gave a new impetus to the then stagnating Assamese literary caravan. ‘O’ Mor Aponar Dex’, accepted today as the state’s anthem is testimony to Bezbaroa’s love for the motherland. His works reflect the traditions of the land, the Vaishnavite cult of Sankar -Madhav and concern for the fragmenting Assamese polity. His lifelong dedication towards the upliftment of the culture, traditions, literature and political state of the region have brought him labels like ‘ A true patriot and nationalist leader’ from critics and fans.

Long research points out that the development of Assamese through time has encompassed several phases. It began from the inscriptions of the Kamrupa kings during the Hindu period of 5th to 12th Century and was followed by later periods by the Charyapada, Shree Krishna Kirtan, Hem Saraswati’s ‘Prahlad Charita’ and the ‘Naam-Ghoxa’ of the Neo Vaishnavite era. Recent waves include the Jonaki age, the Orunoday age and the Raamdhenu age. The current flourish in vernacular literature is all because of the tumultuous times these phases encountered and successfully negotiated. However, the 19th Century was a difficult period for the Assamese language. The end of sex centuries of rule by the mighty Ahoms, the successive invasions by the Burmese and the later capture of the area by the forces of the East India Company lent a severe dent to the pride of the Asomiya. Thereafter in 1836, the adoption of Bengali as the official language marked the coup de grace for the native tongue. A period of stagnation ensued as there was hardly any literature produced in Assamese. This stagnation was multi-fold; the region was slowly getting detached from its glorious past, the good old days when the language, value systems, economic systems stood undisputed. The way India suffered during its long period of colonial subjugation was replicated in Assam. The latter’s pride, glory and rich traditions crushed under the severe blows of imperialism.

This period of crisis was interrupted by the intervention of a few Baptist missionaries from America. Led by enthusiastic men like Nathan Brown and Miles Bronson the missionaries sought to get Assamese recognized as an independent language and to break the popular belief that it was a mere dialect of Bengali, a belief that the new Babus from Bengal and the Bengali intelligentsia were militantly advertising. The missionaries might not have scripted a fairy tale rescue of the swamped Assamese culture as there were few educated natives to join the revivalist bandwagon, but the publication of ‘Orunoday’, the first Assamese journal lent a lease of life to this language threatened by extinction, a condition conjured by the colonial regime. This was followed by a wave of literary growth in Assamese through the works of Anandaram Dhekial Phukan, Hemchandra Barua and Gunabhiram Barua which led to serious reworking of official policies and the year 1873 saw the re-adoption of Assamese as the province’s official language. This resurgence reached a high water mark when a band of Young Turks from Calcutta entered the scene. The Asomiya Bhaxa Unnoti Xadhoni Xobha (The Assamese language development council) was formed over a tea party on 25th August 1888 at the then colonial capital. Under the Garibaldian styled leadership of Laxminath Bezbaroa the council spelt out its aims in clear and unambiguous terms- to craft a terrain for the all-round development of the Assamese language and strive for its enrichment. Thus, a clause for linguistic nationalism was given centre stage in the agenda of the nascent council.

It was through the efforts of Bezbaroa and Chandra Kumar Agarwalla that the council published a magazine ‘Jonaki’. It was through the annals of Jonaki that these young Assamese intellectuals voiced the first clamours of Assamese nationalism. Instead of joining the political struggle for India’s freedom ,Bezbaroa and Co. adopted a more pragmatic approach. For them the meaning of agitation was creative and they felt that though the politics of language and a strong cultural foundation, nationalistic passions would set in and by utilizing this unity forged by a common language and rich culture the Assamese could one day agitate for greater political freedom. ‘Jonaki’ became a revolution of sorts and being ably guided by the devoted Bezbaroa it stood out as the foremost platform for works in the Assamese language to be published. Bezbaroa dominated the literary scene during this period (1890-1940) and produced some of the timeless classics of the age like ‘Joymoti’, ‘Burhi Aair Xaadhu’, ‘Tatva Katha’, ‘Bhodori’.

Bezbaroa was cognizant of the fact that the Assamese nation was nothing short of a confederation of numerous races and religions. His clarion call to the youth was to break the narrow barriers of communal alignment and weave a harmonious ‘Bor-Oxom’ of different communities, races and groups. He exhorted the people to understand the land of Assam by conducting studies on the region’s history, geography, sociology, traditions, indigenous food, customs, monuments and folklore. This was nothing short of a Bismarck like conceptualization. Both luminaries dreamt of a unification of their respective fragmented races. He realized that along with Indian independence, there must be bred a wave of Assamese nationalist sentiments. To this end, two aspects were regarded primal; firstly, development of Assamese language and literature and secondly an expansion of the mass of educated people in Assam.

Bezbaroa for the major chunk of his time lived in Calcutta and Sambalpur, owning a thriving timber business in many parts of the erstwhile Bengal Presidency. Notwithstanding this distance from his motherland, Lakshminath always stayed rooted to his native culture and his love for Assam stayed unquestioned. He was particularly angered by incidents of Non-Assamese trying to subvert the Assamese race through propaganda and intellectual sabotage. A lot of incidents disturbed him. The opening of a school in Tezpur by Bengalis and providing admission to only Bengali students, encroachment of fertile valleys by Bengalis and building colonies overnight, attempts to politically and culturally include Goalpara within Bengal, calling Ananta Kandali a Bengali and zealously propagating that Sankardeva’s religion a copy of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu’s Vaishanavite cult are a few examples. It was Bezbaroa himself who took on the entire Bengali intelligentsia in a lone battle. His duels with many a big name from Calcutta mark the beginning of a new age, a time when Assamese as a language and as a culture gained a position of difference from Bengali. He had once opined, “The infant Assam has begun its campaign to reclaim its lost glory and no attempts of connivance shall be tolerated. At no cost shall we sell our motherland. Before any such exchanges, we shall prefer to perish.”

Bezbaroa’s approach to nationalism was four-fold. For him four aspects were important- religious, social, political and linguistic. His essay “Asomiya Bhasha aaru Sahitya” or “Asomiya language and culture” remains a cornerstone in his granary of political writings where he writes at length how the British colluded with the Bengali intelligentsia in recognizing Assamese as a mere dialect of Bangla. In one of his lectures delivered at the Asomiya Bhasha Unnoti Xadhoni Sabha he writes how and why the British were happy in propagating the lie that Assamese was a mere outgrowth of Bengali. He showed how in Assam, Bengali was imposed as the medium of instruction in schools and was the official language for all administrative purposes. He also accused the Assamese middle class of remaining dumb spectators when all of this was carried out. A language that was so rich and was in use in the written form was suddenly because of colonial invasion reduced to a position of subservience to some other neighbouring language frustrated Bezbaroa.

Bezbaroa believed that a strong culture can only withstand attacks from other groups if it had a durable axis which for him was religion in the form of Neo-Vaishnavism. This Bhakti cult was propounded by Sankardeva in the Middle Ages and gained popularity in the land due to its inclusive and liberal attitudes.

He was never actively involved in India’s freedom campaign and remained a vocal critic of Gandhi on several occasions. He opposed the Swadeshi movement as being impractical and called it myopic. He rather supported Indians receiving English education, learning to trade and set up businesses and industries. Bezbaroa thus envisioned a place where the colonial subjects would one day turn the colonial apparatus against the ones who imposed it on the subjugated races. He had little faith in the politics of the Charkha, favouring the pen, paper and plough.

Culturally, he detested trends of the Assamese trying to ape the English or the Bengali colonizers. Relinquishing the Mekhela-Sador for the Saree, the Pitha for the Mihidana were abhorrent ideas for the nationalist Bezbaroa. He was married into the great Tagore family of Calcutta but was able to keep at bay all temptations of ‘Banglafication’. Even on his dinner table in Sambalpur, could be found platters like ‘Kahudi’ (‘Mustard sauce’), ‘Poita Bhat’ (‘Fermented rice’) and Pitha (‘Rice Cake’).

For Bezbaroa, nationalism was not a synonym for parochialism. It was the name given to the idea of liberating one’s country from foreign domination and not xenophobic designs of warring against other races. He loathed friction amongst communities and clamoured for universal humanism. This marks a visible departure from mainstream notions of nationalism and patriotism. For Bezbaroa, nationalism was to be inclusive which would do good to subjugated races rather than pit one against the other. Bezbaroa was arguably Assam’s first nationalist who through his works set into motion a long-drawn process of cultural self-assertion. The nascent process of establishing Assamese as a distinct linguistic and cultural group started by the Evangelists in the 1830’s met with fruition with Bezbaroa’s foray into the socio-literary scene. Post the ‘Bezbaroa era’ emerged the final and the most complete wave of Assamese literary and cultural assertion that continues till date. His efforts to towards this shall always be remembered by the people who have inherited the Brahmaputra-Barak valley as their motherland.

©Project Lipyontor, Translation by: Shakya Shamik for enajori.org